From Wounded Knee, Guided By a Sacred Drum

This story below, in which I follow a group of water protectors and activists who’d traveled across the country in an old yellow school bus to drum for Leonard Peltier’s freedom, was slated to be published in January 2017, during inauguration week. It was killed by the magazine after Peltier’s clemency was again denied. Now that Peltier has at last been released from 50 years of incarceration (on house arrest, not a full pardon), I am sharing it here, with gratitude to generations of activists and legal workers and others who advocated tirelessly and worked behind the scenes for decades.

by Rebecca Bengal

Brooklyn, New York. April 16, 2024.

On December 6, two days after the Army Corps of Engineers announced that it had denied a crucial construction easement to the Dakota Access Pipeline, the drum left the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota during a break in a blizzard. It then traveled nearly 1,800 miles to New York City by way of Washington, D.C., in a yellow school bus from a whitewater rafting company. With the drum were more than a dozen water protectors from the resistance camps at Standing Rock, as well as Japanese Buddhist monk and peace activist Rev. Dr. Yusen Yamato; and Mike Davis, a Taos, New Mexico-based grassroots organizer who had bought the bus from a relative of Che Guevara for a dollar. On the drive out East, the bus broke down four times.

It was the drum’s first cross-country trip, the bus’s second to Washington. A year before, Davis had driven the bus to D.C. for the same purpose, to participate in a vigil for the clemency of Leonard Peltier, the long-incarcerated former American Indian Movement activist. Say “Wounded Knee” and you could be referring to the 1890 massacre that took more than 150 Lakota lives or of the 71-day siege in 1973 that claimed several lives and unleashed three years of violent unrest on the Pine Ridge reservation. As Ian Frazier wrote in his 2000 book On the Rez, “The history of the Lakota over the last 150 years hangs on those two dates like wire on telephone poles.”

In the midst of what became known as the Reign of Terror that descended in those years on Wounded Knee and Pine Ridge was the 1975 deadly shootout in which two FBI agents and one Native American man lost their lives. Peltier, who was convicted in the deaths of agents Jack Williams and Robert Coler, has long maintained his innocence. During Peltier’s more than 40 years of incarceration, letters and petitions urging his clemency have come from Amnesty International, from the Dalai Lama, Desmond Tutu, Mother Teresa, and Coretta Scott King, from Noam Chomsky and Harry Belafonte, from Peter Matthiessen, who wrote about Peltier in a book In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, and from Kurt Vonnegut, from Rose and William Styron, and, recently, by a former U.S. prosecutor in Peltier’s case. Apart from Mumia Abu-Jamal, there is perhaps no person within the American mass incarcerated system whose freedom has been called for as widely as Peltier’s, and his clemency appeal has taken on renewed urgency during President Obama’s final days in office.

Within the resistance movement at Standing Rock, Peltier is regarded as a hero. In a September statement of solidarity he wrote, “Along the lines of what Martin Luther King said shortly before his death, I may not get there with you, but I only hope and pray that my life, and if necessary, my death, will lead my Native peoples closer to the Promise Land.” Currently held at a federal prison in central Florida, he is 72, a diabetic with heart disease who is in severely ailing health. In December, the drum and its drummers and singers arrived in Washington, D.C., just in time to play at a vigil for his freedom.

To the Lakota people, the drum is sacred; it is a living entity, a heartbeat. Playing it is a way of summoning the spirits of the ancestors. In part because its songs are handed down through oral teachings, the drum is an important link between the present and past. And because the filming and taping of Native American ceremonies is highly discouraged, if not altogether forbidden without explicit consent, publicly available recordings of Lakota prayer songs are rare. (The label Canyon Records and Smithsonian Folkways have, however, released a few, as has Lakota Books, a small independent label and publisher based in New Jersey.) Ceremonial songs are passionate, and formal: thunderous drumming or a ruffle drumbeat accompanied only by voice. At Standing Rock in October, when I would ask for a translation of lyrics, the answer was often “it’s a song for the water” or “it’s a song for the earth.” In other words: don’t overthink it. When I returned six weeks later, the songs had become familiar, reverberating from the central fire. And when I heard the drum in New York, it seemed to summon that same smoke.

The drum that traveled from Wounded Knee measures the width of a small table, large enough to accommodate a circle of many drummers. It was made by hand of buffalo hides stretched and laced over cottonwood, a laborious and unglamorous process. When it was completed and presented for the first time at a ceremonial sundance in Wounded Knee last summer, it was blessed in the Lakota tradition, and given the name Ta Oyate Olowan, “The People’s Songs.”

“It goes where it is called,” said the drum’s keeper, Wakinyan Little Moon, on a frigid December afternoon in Manhattan. Little Moon is from Wounded Knee. He is 17. He wore his long dark hair pulled back, underneath a beanie. His demeanor is steady and calm and a little bit shy. Over the course of the day he never let the drum out of his sight. He declined offers to help transport it, even though that meant maneuvering it for twenty city blocks. The wind chill on that particular day hovered between five and ten degrees, and Little Moon wore no gloves. Outside the United Nations building, where the drummers and their group had just presented songs and letters urging Peltier’s clemency to the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Little Moon wrapped the drum in an imitation Pendleton blanket, and hoisted it over his head.

The United Nations, New York City. December 2016.

“You’re going to get buff carrying that thing around,” said Challenger Emerson Little Elk, a 20-year-old singer from the Rosebud Sioux reservation who met Little Moon at Standing Rock.

“I am buff,” Little Moon corrected him, cracking a small smile.

“Wakinyan!” called Mike Davis, and Little Moon and Little Elk stepped up their pace to catch up to the others.

Tall and gangly and still bearing the surfer-hoarse accent of his California childhood, Davis has the unflagging, but chronically sleep-deprived energy of a lifelong activist and a youngish dad. The day before he had managed the New York City miracle of parking a school bus on the street twice in an afternoon without getting a ticket; today he was shepherding everyone on foot from an apartment in Bed-Stuy to an Airbandb where the day’s Defund DAPL action was being planned, with the meeting at the United Nations en route.

It was, in many ways, a familiar route, one marked with flashes of hope, but few successes. In 2000, when Bill Clinton was about to leave office, there were strong signs that he, too, might free Peltier. That year, Davis joined the Global Peace Walk, a movement begun by Rev. Yamato in 1990; the participants walked across the country from San Francisco to the White House. On Indigenous Peoples Day in 2000, together with Chief Arvol Looking Horse, Leonard Crow Dog, and six other tribal chiefs, they met with Clinton to appeal for Peltier’s clemency; and they went to New York to speak with the United Nations on the U.N.’s 55th anniversary. That was October 2000. Two months later, some 500 active and retired FBI agents marched on the White House wearing pins that read “Never Forget.” When Clinton commuted or pardoned the sentences of 140 persons on his last day in office, Peltier was not among them.

Though the outcome of that year did not turn things in Peltier’s favor, Davis was undeterred; that walk was the beginning of a trip he continues now. “We’re completing a circle. To me, Leonard Peltier, Standing Rock, it’s all part of the same thing, global peace, and that is what I’m here for,” he said. “That 2000 walk was my introduction to the Red Road.” We were walking south on First Avenue in a long snaking line that included Davis’s two children, who are 14 and 10, and his group of bus riders. At each intersection, he stopped and checked to make sure no one had been lost.

When Davis went back to Taos after that first walk, he continued his organizing work, and began attending sweats. Five years later, he was invited by a singer on the Porcupine reservation to come sing Lakota songs. “I’m just grateful to the Lakota Nation for inviting me into that tradition,” Davis told me. “Someone with a critical mind may listen and say, oh they’re just native chants and this is part of their culture. And they are chants and it is a part of their culture. But it’s also more than that. It’s a very disciplined, strict teaching; it’s very serious, very sacred. If these songs are treated right, they are spirit helpers. And the Lakota have so much heart, they’re super cool and super hard core.”

December 2016.

Little Elk, who had ducked into a bodega to buy a dozen roses for his girlfriend, Jasmine Le Beau, rejoined us. He is 20, he wears the trace of a mustache; he is alternately boastful, sarcastic, sincere. When he sings, though, his voice is strong and unwavering. “You sing with power,” he said. “I’m talking singing with your soul; you gotta sing it where people can feel it. My job is to do that. I sing nice and hard and I try to make it for everyone.”

I had met Little Elk and Le Beau at Standing Rock in October at the nightly drumming ceremonies, and when I returned to camp in December, I immediately recognized his singing voice in the dark, ringing out across the Cannonball River. Both Little Elk and Le Beau had come to Standing Rock at the end of the summer; each meaning to stay only a couple of days. At camp they met and fell in love. The bus trip was the first time they’d left since. “We’re here for Leonard Peltier, and we’re here to inform people about the pipeline, and the banks that have their money in it,” Le Beau said. She is an aspiring lawyer who deferred her collegiate studies to stay at camp. Back home on the Cheyenne River reservation in South Dakota, she sang prayer songs at school Friday afternoons.

“We grew up singing, and that’s how we learned to stay connected, so it’s a privilege to sing for camp and keep them in prayer,” Le Beau said. “He and I both come from bad backgrounds, and we do have a spiritual connection. Our towns, and how people grow up, sometimes it’s tough. Sometimes, though, hearing him sing, I’m like, I don’t even have to pray anymore. I’m like, ‘sing that shit, baby!’” She swiveled her head and laughed, clasping her bodega bouquet in one hand and Little Elk’s in another.

“The songs are prayers themselves,” Little Elk said. “Most songs will say ‘pity me,’ which isn’t a bad thing, but more like, ‘think of me, look upon me.’ Most songs are asking the Great Spirit for help.”

“The one that talks about the oyate, about the people’s struggle, that one’s my favorite,” said Le Beau. She sang a lyric in Lakota, clear and radiant and practically visible in the cold air. “When I first heard it at ceremony, my uncle told me that’s for everyone who’s struggling. That’s why I like it, it’s for everybody.”

More than a year ago, Mike Davis got a phone call from Little Moon’s mother, Juliann Shot to Pieces, in Wounded Knee—“We are the real Wounded Knee here,” she told me recently by phone, describing their tiny community of 1,000 people. “History surrounds us on all sides.” When Wounded Knee appeared in the news, it was often in conjunction with the larger stories of Pine Ridge, where, since December 2014, there had been an alarming rise in youth suicides. In the space of four months, nine young people between the ages of 12 and 24 had taken their own lives. Nearly a hundred had attempted to kill themselves. A New York Times article enumerated the possible reasons: poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, bullying. “To be Lakota in this world is a challenge because they want to maintain their own culture, but they’re being told their culture is not successful,” Ted Hamilton, a local school superintendent, told the Times.

Stories like the ones in the Times were equally frustrating, Shot to Pieces believed. “We have a lot of good kids in the community. They don’t get in the news.” Her son was one of them. “He was always different,” she said. “He followed the Red Road from an early age.” In the winter of 1998, her husband died; that same winter Little Moon, then only 7 years old, began singing traditional Lakota Sundance songs. At 16, he would still be considered a young drummer—the teaching of Lakota music can take years—but his mother saw it as an opportunity not only for her son, but for the rest of Wounded Knee too.

“Around here, the boys and young men like to call themselves warriors,” she said. “But a warrior doesn’t only fight, he helps his people. And a drum can bring people together. It calls them and draw them in.” To become keeper of a sacred drum, no matter what age, would signal both a privilege and responsibility and continue a connection to Lakota culture.

Through a mutual friend, Shot to Pieces got Mike Davis’s number and called him to see if he could help. Moments after they hung up, Davis had pulled over at a service station, where he happened to see Lee Lujan, a Willow Nation Apache traditional drum maker, walk past his car. The coincidence was too great not to act on it, even though he was nervous as he approached Lujan. To Davis’s amazement, though, he agreed to make a drum.

Soon Davis found himself calling on the aid of traditional Lakota singers he knew, and then driving a pickup truck to Colorado filled with a cottonwood log carved by Lujan and green buffalo hides, riddled with maggots, which he spent the coming days scraping clean—“really nasty,” Davis remembered. By summer, the drum was finished and ready for its first calling: It was blessed by a Lakota leader Gerald Ice, in a sundance in Wounded Knee and presented to Little Moon.

December 2016.

Not long after the People’s Songs was given its name, it was called to Standing Rock. Into the yellow school bus went elders and youth from Taos and Wounded Knee and Porcupine reservations and elsewhere. The drum was played at the central fire and it was played on the frontlines. On November 2, when water protectors at Standing Rock crossed the freezing Cannonball River to pray at a sacred Sioux site, Turtle Island, the drum was played in ceremony, in a canoe. Police responded with rubber bullets, tear gas and mace. Was the drum also maced? I asked Little Moon. “The drum was maced,” Little Moon said, wincing slightly. He had been unable to shield it.

The drum’s calls continued. Later in November, the drum was invited to play in memoriam, in honor of the late Santee Dakota activist and poet John Trudell. On December 4, when the Army Corps denied Dakota Access a final easement to construct under the Missouri River, the drum was played in celebration around the central fire at Oceti Sakowin camp, surrounded by thousands, including an influx of military veterans who had come to offer support that weekend. A day later, when a blizzard hit, and many of the veterans found themselves taking overnight shelter in the concert pavilion of a nearby casino, the drum was one of six that played at a forgiveness ceremony among veterans and Native Americans, led by Lakota Chief Leonard Crow Dog.

While DAPL construction was officially halted pending an environmental review, the pipeline resistance focus shifted to defunding the investors in the pipelines. Organizers in a borrowed Midtown residence, many of them who had traveled from camp, went over a late afternoon plan to “shut down” a succession of bank locations. Little Moon and Davis exchanged a worried look, and Davis spoke up. “Nothing can happen to the drum,” he said. “We’ll take care of the drum,” promised the Bronx musician and activist Immortal Technique. Little Moon hunkered closer to the drum, almost as if he were whispering to it.

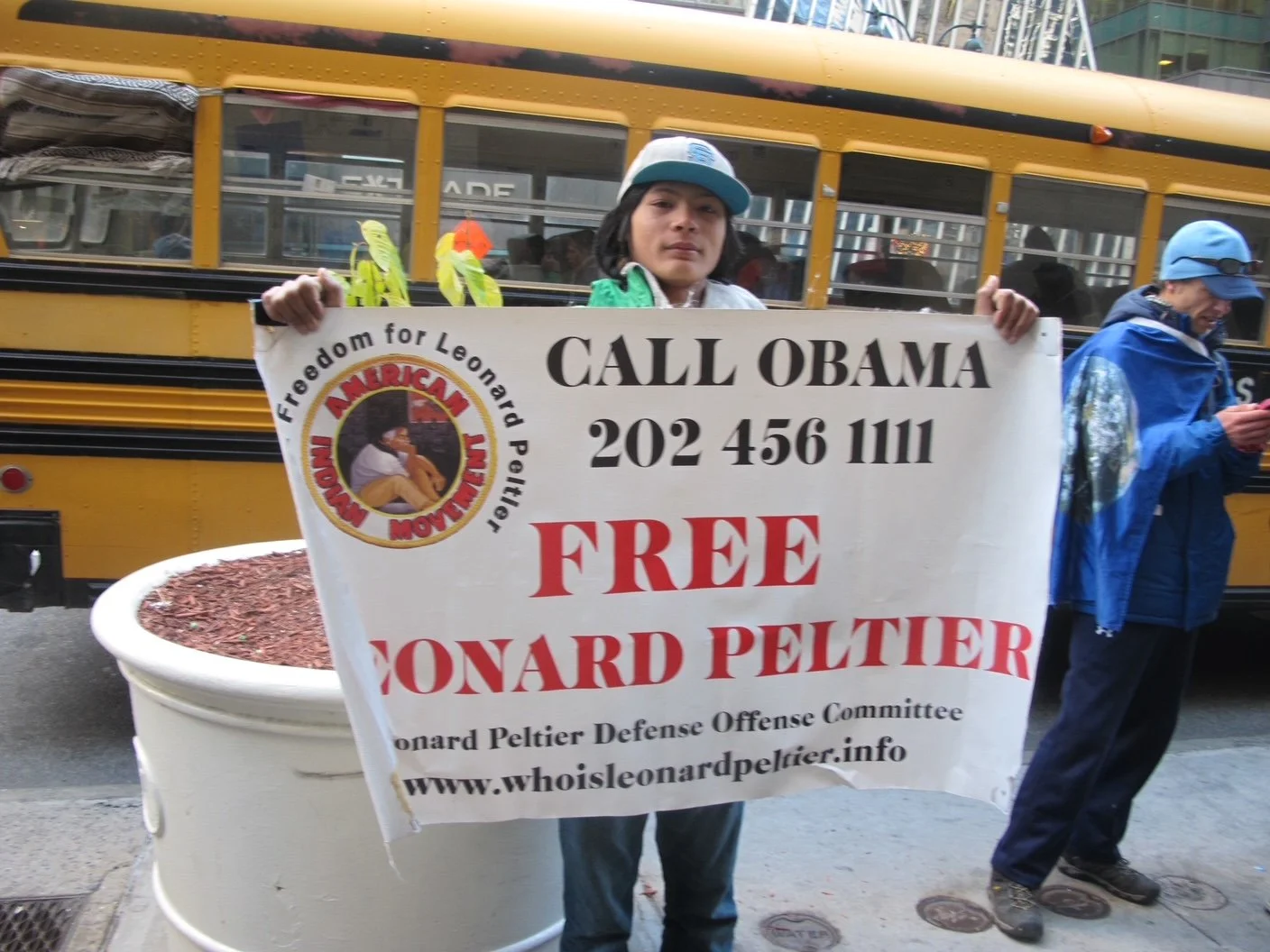

Crossing Park Avenue, before they unfurled banners reading Defund DAPL and Free Leonard Peltier, the drummers were recognized in the street. “Are you guys from Sacred Rock?” asked one passerby, apparently confusing the name of the Standing Rock tribe, and one of the resistance camps, Sacred Stone. Rudell Bear Shirt, a 50-year-old drummer from Wounded Knee, returned a huge smile. “Yes!” he said emphatically. “What are you doing right now? Join us!”

The drum was played in the lobby of Bank of America on Thirty-fourth Street and Fifth Avenue, as a representative from Honor the Earth addressed customers waiting in line on a bullhorn; it was played in the middle of Thirty-fourth, temporarily halting traffic, as Chase Iron Eyes, a leader in the resistance camp who ran an unsuccessful bid for Congress in November, danced in the street, dressed in a suit, his long braid swinging behind him. The drum was played by the ATMs across Fifth Avenue at a Chase location, as confused tellers stood behind doors protesters had sealed over with yellow caution tape. By the time the delegation reached the third location, a TD Bank on Thirty-third and Park Avenue, they had attracted a police escort of sorts. The TD lobby was capacious and high-ceilinged; particularly good acoustics for the drum. An employee on the upper floor took out a cell phone, recording the scene. At Citibank, the last financial institution of the day, allied protesters had joined the group. In the lobby, a small scuffle ensued; at least one person was handcuffed and led away. As more police cars and vans pulled up to the curb, Little Moon, looking nervous, edged the drum back from the crowd and further up the sidewalk; the drummers followed, continuing their song.

December 2016.

Rev. Yamato was sleeping off a fever in the borrowed Midtown apartment; the group’s host had taken off to go to one of his jobs, working sound at a club in Brooklyn; Davis was starting to wonder aloud about the logistics of getting everyone fed and safely home. The night had grown especially cold, acknowledged even by those who had weathered subzero temperatures at camp who walked a little faster to the next destination. The police on foot behind them walked a little faster too. The sense of urgency and fear in the air became palpable.

“I feel like, spiritually, the light and the dark are present,” Davis said as we walked north on Park. A well-heeled couple stopped and stared at the passing drum. Down the block, a woman took a picture. “So when you have this beautiful reunification that’s happening at Standing Rock, bringing First Nations and people from all over the world together, it makes perfect sense that you would now also have a fascist president come in. The evil rears its head as the good is shining so bright.”

The next afternoon the drum would board the yellow school bus again, to start the journey back, dropping off some at camp in Standing Rock, at home in Porcupine, Rosebud, and Wounded Knee. Before leaving New York, the drum would play in Peltier’s support once more, in a taping on Democracy Now!, a recording that Peltier himself, still awaiting word, would ostensibly be able to hear. When it became unlikely that Obama would grant his clemency, he issued the following statement: “If I should not [receive clemency] then after we are locked in for the day I will have a good cry and then pick myself up and get myself ready for another round of battles until I cannot fight [any]more. So, don’t worry. I can handle anything after over 40 years.” In the days before Donald Trump took office, when President Obama issued his final clemency grants, Peltier’s name was not on the list.

On December 15, in the middle of rush hour, the drum completed the day’s circle at Grand Central Station. As commuters whisked by, a banner was unfurled in Great Hall. Taking their places around the drum, the drummers glanced over their shoulders at the police who had gathered nearby, arms crossed. Little Moon lifted his drumstick and struck first, a thunderous sound that rose to the top of the starry, constellation-painted ceilings.

Brooklyn, New York. January 19, 2024.